Student

Union

Building

3rd

floor

6136,

University

avenue,

Halifax,

NS

B3H

4J2

Canada

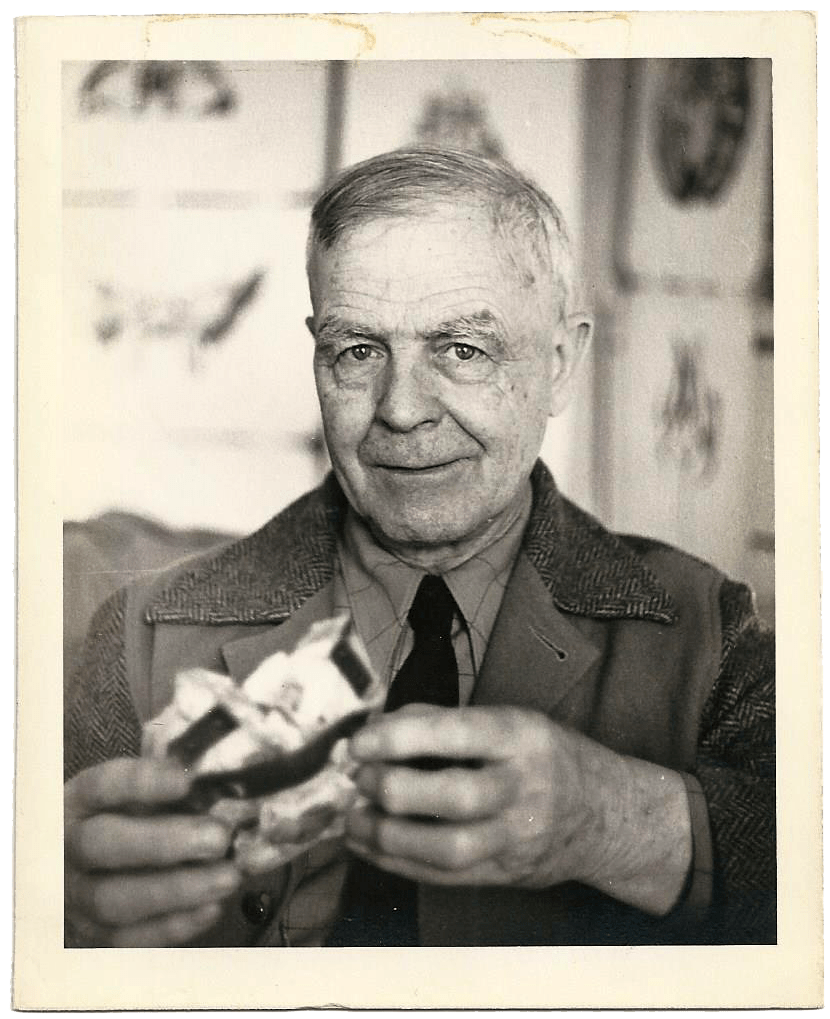

Class of 1909 with Doctor Andrew Taylor Still

Tradition, Research and Know-How

A.T.

Still

founded

Osteopathy

on

June

22nd,

1874

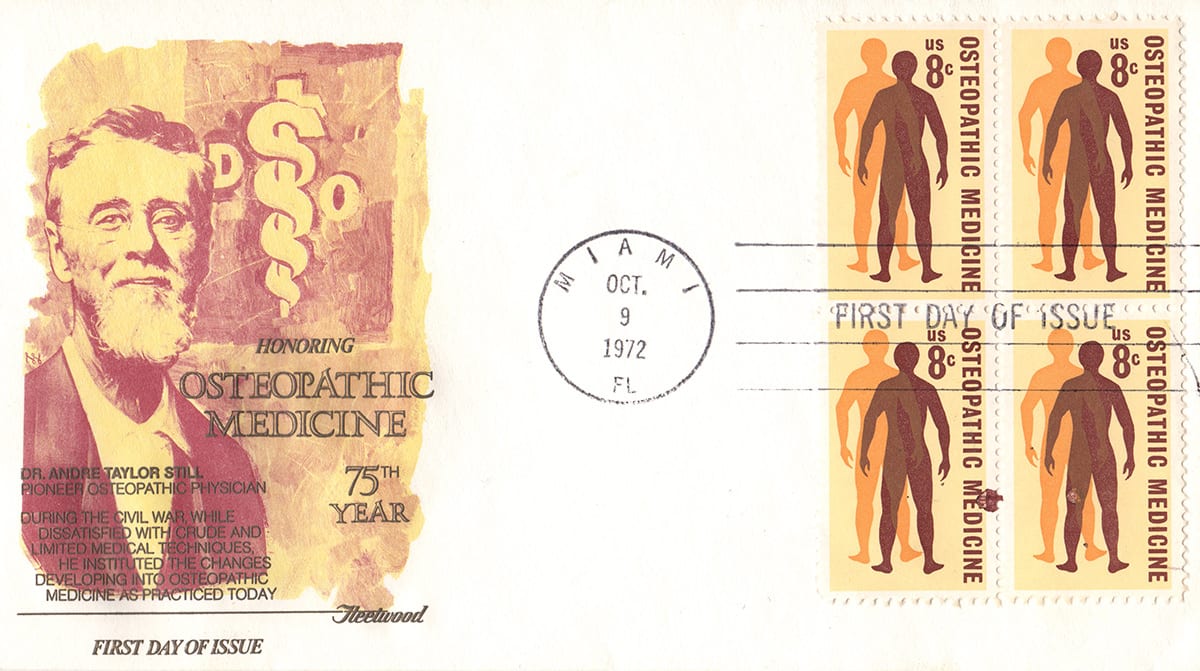

Commemorative stamp marking the 100th anniversary of osteopathy

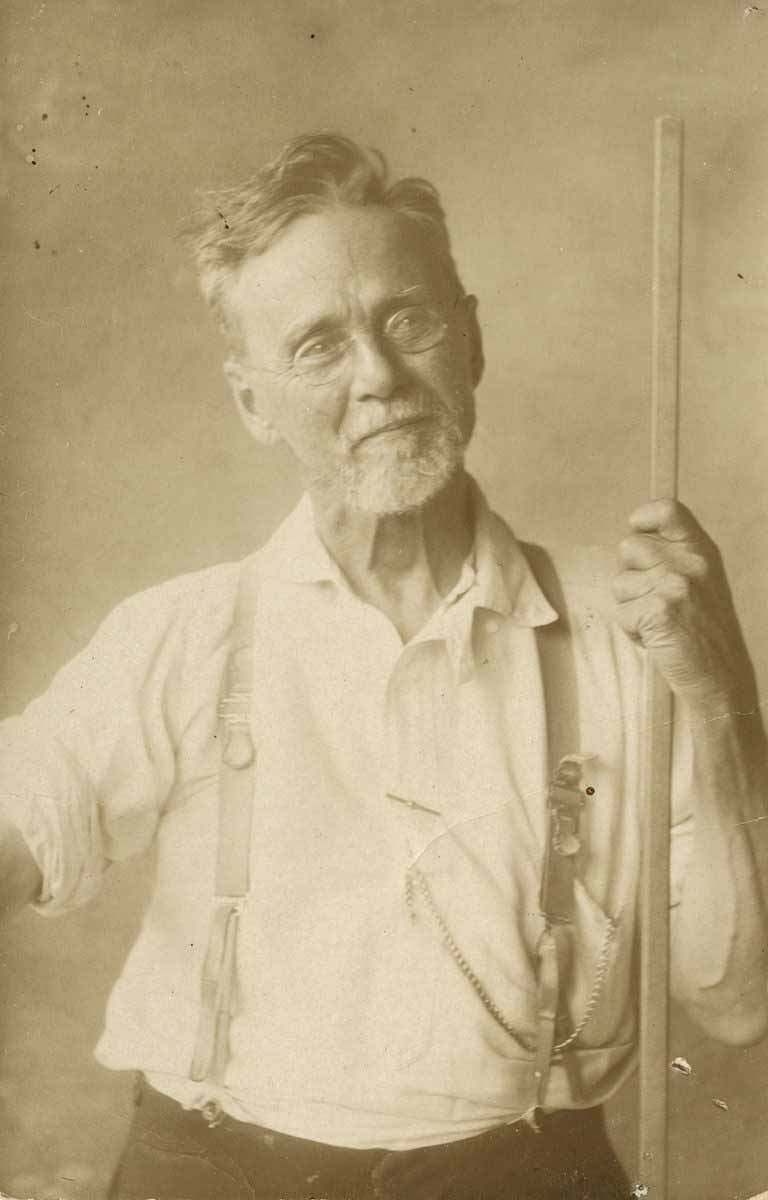

The founder Dr Andrew Taylor Still - Transmission generation to generation

The first cranial course in Paris in 1965 - Thomas Schooley D.O., Viola Frymann D.O., Harold Magoun D.O., Denis Brooks D.O.

The day of the success to get Bachelor with honor degree formation validated by University of Wales

Teaching with American DOs at Osteopathic Center for Children.

History of Osteopathy & the College d'Études Osteopathiques, Halifax

Traditional

Osteopathy,

as

presented

by

the

CEO

Halifax,

is

defined

as:

“A

natural

manual

therapy

which

aims

to

restore

function

in

the

body

by

treating

the

causes

of

pain

and

imbalance.

To

achieve

this

goal

the

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioner

relies

on

the

quality

and

finesse

of

his/her

palpation

and

works

with

the

position,

mobility

and

quality

of

the

tissues.”

The

osteopathic

philosophy

embraces

the

notion

that

the

body

is

naturally

capable

of

healing

itself.

The

practitioner

of

traditional

Osteopathy

works

with

the

body

to

enhance

this

natural

ability

to

self-regulate

and

self-heal.

Palpation

(sometimes

referred

to

as

listening)

is

a

diagnostic

skill

that

the

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioner

uses

to

feel

or

sense

the

state

of

the

tissues

or

systems

being

examined.

This

sense

encompasses

the

many

sensory

aspects

of

touch,

such

as

the

ability

to

detect

moisture,

texture,

temperature

differential,

and

subtle

motion.

The

ability

to

detect

almost

imperceptible

motion

provides

the

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioner

with

the

capability

of

perceiving

the

inherent

motion

present

in

all

living

organisms.

This

palpatory

ability

is

not

a

gift—rather,

it

is

a

trained

skill

that

takes

years

to

develop.

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioners

palpate

by

gently

yet

intentionally

touching

the

tissues

or

systems

under

examination.

With

experience,

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioners

learn

to

palpate

not

just

superficially,

but

also

very

deeply

within

the

body.

Sensory

information

is

received

through

touch

receptors

in

the

fingertips

and

palms,

as

well

as

through

the

proprioceptors

(motion

and

position

sensors)

embedded

deep

in

the

joints

of

the

hands,

wrists,

arms,

and

even

the

shoulders.

The

ability

to

detect

minute

modifications

in

the

quality

of

the

tissues

is

the

assessment

skill

that

allows

the

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioner

to

prioritize

a

patient's

course

of

treatment.

These

tissue

qualities

include

congestion,

dehydration,

scarring,

stiffness,

density,

and

loss

of

resilience,

as

well

as

motility,

which

is

an

infinitesimal

movement

inherent

to

all

living

tissues.

It

is

this

sensing

of

the

quality

of

the

tissue—in

combination

with

the

position,

mobility,

and

vitality

of

the

tissue—that

allows

the

Osteopathic

Manual

Practitioner

to

determine

the

tissues

or

systems

that

need

immediate

attention.

History of Osteopathy

The

profession

of

Osteopathy

was

founded

single-handedly

in

1874

by

an

American

physician,

with

a

mechanical

background,

named

Andrew

Taylor

Still

(1828-1917).

Still

was

the

third

son

of

a

pioneer

doctor,

under

whom

he

apprenticed

at

the

close

of

the

Jacksonian

era

(1829-1837).

It

was

a

time

that

encouraged

independent

thought

and

the

development

of

new

disciplines

to

improve

the

lot

of

mankind.

Following

Still's

participation

in

the

American

Civil

War,

he

began

an

empirical

study

of

the

human

body

under

the

premise

that

by

studying

“God's

work”

he

would

have

a

greater

understanding

of

his

“Creator.”

Still

disdained

the

common

practices

of

physicians

in

the

1800s,

such

as

venesection,

emesis,

and

sedation

with

narcotics.

He

believed,

instead,

that

everything

necessary

to

sustain

human

life

was

already

present

within

the

human

body.

Still

sought

to

find

non-medicinal

and

non-surgical

avenues

to

enhance

the

body's

innate

ability

to

heal

itself.

Still

focused

on

mechanical

removal

of

the

impediments

to

the

free

circulation

of

fluids

and

the

elements

carried

within

those

fluids.

He

believed

that

once

these

“mechanical

blockages”

to

the

free

flow

of

fluids

were

removed,

the

free

circulation

of

all

the

fluids

of

the

body

would

naturally

return.

The

free

flow

of

fluids

was

Still's

key

to

the

self-regulation

and

self-healing

processes

of

the

body.

Still's

application

of

this

philosophy

and

methodology

proved

successful

in

treating

musculoskeletal

problems,

as

well

as

the

major

diseases

of

his

era,

such

as

tuberculosis,

pneumonia,

dysentery,

and

typhoid

fever.

Still's

work

was

transmitted

through

writings

that

were

primarily

philosophical

in

nature.

However,

he

also

described

two

main

practical

techniques.

One

focused

on

restoring

the

“position”

of

the

bones

in

relation

to

one

another.

The

other

restored

the

“place”

of

the

organs

in

relation

to

the

major

vessels

and

neural

centers

of

the

body's

cavities.

These

two

systems

are

now

known

as

osteo-articular

adjustments

and

visceral

normalization.

The

first

school

of

osteopathy

was

opened

by

Still

in

Kirksville,

Missouri

in

1892.

Several

of

his

original

students

later

enhanced

the

profession

through

the

introduction

of

other

manual

techniques,

such

as

cranial-sacral

therapy

and

fascial

release.

By

1910,

it

was

recommended,

through

sponsored

reports,

that

osteopathic

colleges

within

the

United

States

adopt

a

system

of

higher

education,

licensing,

and

regulation.

By

1930,

through

a

staggered

transition,

the

American

osteopathic

profession

adopted

a

medical

model

of

osteopathic

education

that

incorporated

all

conventional

diagnostic

and

therapeutic

practices

of

medicine,

including

pharmacology,

surgery,

and

obstetrics.

For

this

reason,

all

graduates

from

osteopathic

colleges

and

universities

in

the

United

States

are

fully

licensed

medical

physicians

and

are

recognized

internationally

as

Osteopathic

Physicians.

The

rest

of

the

world—including

Europe,

Asia,

Canada,

and

the

countries

of

the

Southern

Hemisphere—has

not

adopted

this

medical

model

of

Osteopathy.

Instead,

their

curricula

focus

primarily

on

the

manual

application

of

traditional

osteopathic

philosophy

and

principles.

In

1917,

Osteopathy

took

root

in

Europe

thanks

to

Martin

Littlejohn,

DO,

a

student

of

Dr.

Still

and

a

professor

at

the

Kirksville

osteopathic

school.

Littlejohn

founded

the

British

School

of

Osteopathy,

which

remains

active

today

under

the

name.

In

France,

the

origin

of

Osteopathy

has

been

traced

to

Major

Stirling

in

1913.

The

Collège

d’Études

Ostéopathiques

(CEO)

was

founded

on

March

11th,

1981

in

Montreal

by

Philippe

Druelle,

D.O.,

an

osteopath

trained

in

France,

assisted

by

Dr.

Jean-Guy

Sicotte,

MD,

D.O.

This

college

was

the

first

of

its

kind

in

Canada

to

offer

a

comprehensive

program

and

teach

traditional

manual

osteopathy.

Associated

colleges,

including

the

DOK

in

Germany

(1991),

the

CCO–Toronto

(1992),

the

CEOQ

in

Québec

City

(1996),

the

CSO-Vancouver

(2001),

the

CEO–Halifax

(2002),

SICO

in

Switzerland

(2002)

and

CCO–Winnipeg

(2010),

were

subsequently

established.